Robert Traill and His Writings

Readers will be interested to know that the Trust is soon to re-issue Robert Traill in two volumes. There are a number of reasons why Traill deserves to be reprinted. First, his long and active life spanned the period of the Puritan Age. Born in 1642, almost on the eve of the Westminster Assembly, he passed his early years in the Cromwellian era, was exiled to Holland at the Restoration and, on returning to Britain, settled into the Presbyterian ministry in the south of England. Traill rubbed shoulders with all that was best in the Scottish, Dutch and English Puritan traditions.

Secondly, Traill is eminently spiritual and edifying. If some of the Puritans who have come down to us may at times be chargeable with an excessive addiction to ‘branching’ sermons, to Latinisms, to heaviness of style, to contemporary allusions now obscure to men, or to a tendency to spiritualisation, Traill is almost entirely free from such charges. Schooled basically in the Scottish tradition, he concealed his theological erudition under a cloak of true modesty and, crucifying all artistry and literary effect, he strove to open up the naked word of God in homely idiom. His aim was to expose the heart of his hearers to the scrutiny of God alone. The modern reader of Traill therefore will not find him quaint or liable to jar on one’s exegetical finesse.

There may perhaps be even a certain timeliness in this reissue of Traill — a timeliness for the friends of the Reformed movement. He was not primarily concerned to be an academic theologian (though his ability would have qualified him to have aspired to this); nor was he even a writer really at all (though he highly valued the writings of his Reformed brethren). Practically his whole effort was made in the pulpit and from the pulpit, so that what remains to us of Traill’s labours consists almost wholly of sermons — and sermons, too, preached for a particular congregation, with no eye to publication at a later date. Indeed he was so far from ‘rushing into print’ that sermons for the press had to be (in his own phrase) ‘extorted’ from him. Yet in these choice sermons, rescued from oblivion by the affectionate labours of short-hand note-makers who heard him, he furnishes us with so many models of what a sermon ought to be. It could be that our greatest quest as a generation should be for the recovery of Traill’s gift of conveying powerful thought in simple diction from the pulpit.

It could be also that we have something to learn from Traill’s whole ministerial thrust and emphasis. His sermons somehow carry one along with them by the sheer force of truth. One takes up the sermons in order to see the preacher; one lays them down at length having had a glimpse of one’s own heart. You start to read as a critic; before long you find you are cringing away from the preacher’s keen scrutiny of yourself. Not that Traill is predominantly stern, still less severe, least of all fulminating. On the contrary, his spirit is quite even and serene. But he prints in indelible ink and is a holy man. His sword slays not because he is full of fury but because of his nearness to God. In the day when we recover his secret we may see the tide turn.

No adequate life of Robert Traill has appeared to date and the materials for composing a sketch of his long and active life still have to be drawn from scanty notices prefaced to his collected works or from similar sources.

We learn from the prefaces that the Traill (or Trail) family of Fifeshire first emerged from the mists of antiquity around the year 1385 when we hear of one Walter Traill, created Bishop of the Metropolitan See of St Andrews by King Robert II. Two hundred and fifty years later, the name of Robert Traill, father of the subject of this memoir, is indissolubly linked with the mighty who espoused and championed the Reformed cause in Scotland in the seventeenth century.

This elder Robert Traill was minister of the Greyfriars Church a little above the Grassmarket of Edinburgh. Both places are historic, the former as the scene of the signing of the 1638 Covenant; the latter as the place of execution for many a field-preacher.

The younger Robert Traill, the subject of our present concern, was born in Elie, Fifeshire, in May 1642. Here his eminent father was labouring in his first charge. His early education had been supervised by his father who evidently poured his son’s mind and heart into the perfect mould of truth. Only a few years later the young Robert entered the literary and theological classes of the still young Edinburgh University, there to obtain distinction. He gave himself while still young to the Lord and set his heart on the work of the gospel-ministry. It is of interest to us to know that he early became intimate with William Guthrie of Fenwick in Ayrshire (author of The Christian’s Great Interest). Much later he was to accompany the latter’s cousin, James Guthrie of Stirling, to the scaffold — Cromwell’s ‘short man who could not bow.’

There could have been little in the Traill household to conduce to boredom in these early years. The Civil War witnessed the elder Traill as a chaplain in the Scottish army in England, in which capacity he was present at the Battle of Marston Moor. He visited the Marquis of Montrose in prison. Still later, as the current of events ran its ironic course, the elder Traill was one of that party of honest men sent to remind Charles II at the Restoration of his obligation to keep the Covenant. For this good service he was exiled.

With the head of her home banished to Holland, Mrs Traill, nee Jean Annand, was left to care for the children alone. In 1666 the agents of the prelatical party discovered copies of a proscribed book, An Apologetic Relation, in their home and the whole family was compelled to lie low for some time. The crisis, which culminated at the Pentland Rising, in the course of time affected the younger Robert Traill in common with others of his persuasion. Accused of having taken up arms with the insurgents he was compelled to flee to Holland in 1667 to join his father and the whole bright galaxy of British divines sheltering from the storm of Stuart Absolutism, Here he continued his theological studies and helped Nethenius, Professor of Divinity at Utrecht to prepare for the press Samuel Rutherford‘s Examination of Arminianism.

The younger Traill returned to Britain not long after, for we find him preaching in London in April 1669, now evidently ordained by Presbyterian ministers of that metropolis. For a while he ministered in the Presbyterian church at Cranbrook, Kent. But more trouble was in store for him.

In spite of the stringent laws in force against conventicles, he preached privately in Edinburgh, when on a visit there, in 1677. Summarily arrested and brought before the Privy Council, he was condemned to the Bass Rock, partly for having conversed with John Welsh of Irongray on the English border. Confined in the dark squalor of the Bass dungeon he met such distinguished prisoners as Fraser of Brea and Alexander Peden. Mercifully, however, his term of confinement lasted only till October of the same year, and on his release he returned to his flock at Cranbrook. After a few years he migrated to a Scottish church in London where he remained till his death in May 1716, aged seventy-four.

Even in his last years, however, there was no cessation of conflict to be granted him. In Non-Conformist circles the winds of change were blowing. Christ’s cause, safeguarded externally after the Glorious Revolution, became now the subject of attack from within. In 1691 the republication of Tobias Crisp’s works accelerated a controversy which finally rent asunder the English Non-Conformist movement. Debate raged hotly round the cardinal doctrine of the very Reformation itself, the doctrine of Justification by faith alone.

It is not necessary to enter into the details of this controversy except to state that, owing to a decline in French theological purity and to Baxterian influence, the older Protestant conception of Justification was in danger of serious distortion. A new view of faith was gaining ground which, in the hands of some Baxterians, was little distinguishable from downright morality. At the same time the orthodox doctrine of Justification was charged with leading to Antinomianism. From this Aeolus’ bog of confusion were very soon to blow those chill gusts which would blight many English Dissenters with Hyper-Calvinism and sweep the Scottish Marrowmen into secession.

Robert Traill, now in his ripe years and held in high esteem, felt compelled to take up his pen. Joining ranks with such notable men as Isaac Chauncy, Owen‘s successor, and the younger Thomas Goodwin, he preached and wrote in defence of the doctrine of Justification, vindicating it from the smear of Antinomianism, In 1692 he published a ‘Vindication’ to this end. Six sermons on Galatians 2:21 — a consummately apt text — survive from this time.

To the modern reader it is a matter of interest to find Traill, in this period of controversy, warmly commending Owen’s treatise on Justification and Stephen Marshall’s Gospel Mystery of Sanctification. Traill picked his way between the differentia of Justification and of Sanctification with studied carefulness. Hence two centuries later we find the evangelical Bishop J. C. Ryle quoting extensively from Traill. He evidently felt that Traill’s lucid distinctions between these two major doctrines were salutary medicine for evangelicals of his day, sick from the new teaching of the Holiness Movement led by Pearsall Smith.

Those who come to handle the sermons of Traill will not be long before they realise his stature as an expository preacher. Eschewing all ‘sermon-craft’ as a later age come to conceive it, he knows nothing of that striving for applause or effect which mangles the plain sense of Scripture. He filed off no sharp edges of his text. In tone generally cheerful, on occasion laconically reproachful of his people’s slow progress, Traill pursues the even tenor of his way, striking out in each sermon to left and right with firm, purposeful strokes like some master oarsman rowing his crew to safety. He has no time to waste. It is good, plain, palatable fare in each sermon, and plenty of nourishment for all in the flock.

It is this pastoral faithfulness which makes these sermons of so long ago relevant and fresh as ever today. What congregations enjoyed from Traill in the seventeenth century, what James Hervey enjoyed from him in the eighteenth and Ryle in the nineteenth, we in the twentieth century are likely to enjoy in the same way.

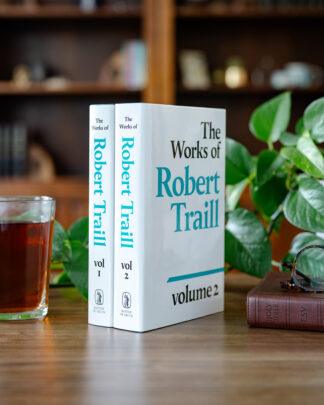

The Trust is releasing a newly typeset edition of the Works of Robert Traill in two volumes. We warmly commend these titles to our readers.

Robert Traill Titles by the Trust

The Works of Robert Traill

2 Volume Set

Description

Readers will be interested to know that the Trust is soon to re-issue Robert Traill in two volumes. There are a number of reasons why Traill deserves to be reprinted. First, his long and active life spanned the period of the Puritan Age. Born in 1642, almost on the eve of the Westminster Assembly, he […]

Description

Readers will be interested to know that the Trust is soon to re-issue Robert Traill in two volumes. There are a number of reasons why Traill deserves to be reprinted. First, his long and active life spanned the period of the Puritan Age. Born in 1642, almost on the eve of the Westminster Assembly, he […]

Latest Articles

On the Trail of the Covenanters February 12, 2026

The first two episodes of The Covenanter Story are now available. In an article that first appeared in the February edition of the Banner magazine, Joshua Kellard relates why the witness of the Scottish Covenanters is worthy of the earnest attention of evangelical Christians today. In late November of last year, on the hills above […]

A Martyr’s Last Letter to His Wife February 11, 2026

In the first video of The Covenanter Story, which releases tomorrow, we tell the story of James Guthrie, the first great martyr of the Covenant. On June 1, the day he was executed for high treason, he coursed the following farewell letter to his wife: “My heart,— Being within a few hours to lay down […]